Where We Live | The Lucy Depp neighborhood: Living black history

By Mark Ferenchik, The Columbus Dispatch

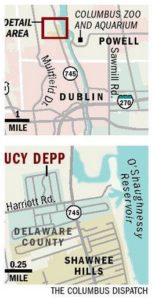

If you drive along Dublin Road past Shawnee Hills in Delaware County, you’ll probably zoom past a sign that reads: “Lucy Depp Park, EST. 1926 by Robert Goode.”

Of course, there’s a story behind the sign, one deeper than you might think. It’s a tale of the Underground Railroad and country living.

And it’s a tale of heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis and an African-American enclave with roots dating back 176 years.

Residents of Lucy Depp have talked to the Ohio Historical Society about placing a marker in the neighborhood of about 65 houses.

Reva Lorenzo recalled visiting the area for her ex-husband’s family reunions, but she knew little of its past. She rediscovered Lucy Depp two years ago.

That’s when she worked for a home health-care agency and visited resident Zelda McDaniel. Intrigued by the area, Lorenzo started to ask questions about the neighborhood and its history. The more she learned, the more she wanted to know.

She has learned so much that she plans to write a book.

Here’s a brief history: Abraham Depp, a Virginia blacksmith, bought 300 to 400 acres in 1835 and started what was Delaware County’s first black-owned farm, said Sandy Wicker, librarian for the Delaware County Historical Society.

The property stayed in the family and, in 1926, Depp’s daughter, Lucy, sold 23 acres to nephew Robert Goode.

Sometime later, Goode bought more land, creating a 102-acre subdivision that he split into 720 lots, some with frontages of only 40 feet.

Some sold for $50, Wicker said.

In no time, it became a summer resort for Columbus’ African-American community, she said. Lorenzo said boxer Joe Louis stayed there, as did prominent musicians who played in Columbus at venues such as the Lincoln Theatre.

William Foster McDaniel, a noted musician and composer, grew up there. He now lives in New York City.

The area was home to many professionals, including doctors.

McDaniel’s sister, Zelda McDaniel, said her family moved to the Lucy Depp community from St. Clair Avenue in Columbus in the 1950s, when she was 9.

“It was all black families at the time,” said McDaniel, pointing to homes nearby and recounting the names of neighbors who lived there.

She said her father drove more than 20 miles to work at B&T Metals in Franklinton at a time when there were no freeways.

McDaniel, who still lives in the Lucy Depp neighborhood, also recalled prejudice when she was growing up. She remembered a teacher at the old Dublin High School telling her class there would never be a black president.

But there were happy times, too. Children played in the pond near the Goodes’ house. A former resident once described it as a “fantasy land” with treehouses and a sledding hill.

The Goode house on Harriott Road remains a focal point of the area. It is home to annual Labor Day get-togethers for the neighborhood, Lorenzo said.

In 1996, Gwyn and Gary Stetler bought Goode’s house, which many believe was a stop on the Underground Railroad.

“It felt like sacred ground when we first walked in here,” said Mrs. Stetler.

How did the Stetlers find Lucy Depp? In the 1990s, Mrs. Stetler was working with a group of senior citizens at the Faith Mission in Columbus’ Downtown. One of them was McDaniel’s mother, Cleona, who invited her to visit the neighborhood.

Now, the Stetlers share their home with church congregations and nonprofit agencies that use it as a retreat, said Mrs. Stetler, director of community life for the Columbus Housing Partnership.

And like the Stetlers, Lorenzo decided she wanted to become a part of the Lucy Depp community.

She moved there two years ago and met her husband, Herman “Bud” Lorenzo, who moved into his mother’s cousin’s house in 1981.

With all this history, residents say they want a marker. In 2009, they spoke with the Ohio Historical Society’s Andy Verhoff, who told them that markers cost as much as $2,400. Lorenzo said the community plans to hold fundraisers to buy one.

“If a community thinks something they want to mark is historically significant, and they want to preserve it, that’s good enough for us,” Verhoff said.

It’s been more than a century in the making.